Photo by: FatCamera/Getty Images

Can HBCU students be the next target of voter suppression?

Lauren Nicks, a senior at the legendary Spelman College in Atlanta, voted in her home state of New York during the midterm elections last month.

Nicks, a 21-year-old international studies major at the historically Black college, had been informed months earlier by other students about a law prohibiting students from private colleges and universities in the state from using their school ID as identification to vote — a provision she believed would prevent her from casting a ballot in Georgia.

“You can’t use that [Spelman] ID,” the Spelman College student said. “I just thought I wasn’t eligible.”

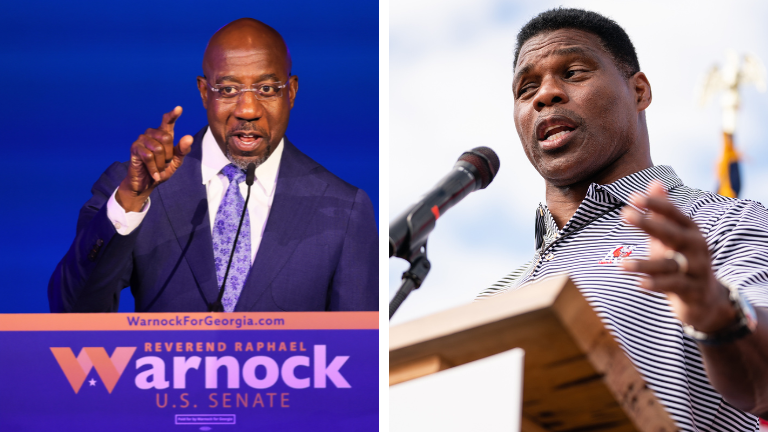

As a result, Nicks was unable to cast her vote for Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock in either the November election or the runoff vote the following week.

This surprise was caused by a 16-year-old Georgia voting law provision that states that the only permissible forms of voter identification are school IDs from public schools and not private institutions.

Voting rights experts claim that this clause continues to confuse voters, particularly college students and other people who already encounter voting obstacles, leading to many of them casting their ballots elsewhere or not at all.

However, they claim that since seven out of ten historically Black colleges and universities in Georgia are private schools, it has an outsized influence on student voters of color.

According to Vote Riders, a nonpartisan, nonprofit group that represents voters in states with severe voter ID requirements, there are approximately 157,000 registered voters in Georgia who do not have an ID number on file with the secretary of state’s office.

The quantity was verified by the Georgia Secretary of State’s office. In Georgia, private HBCUs enroll at least 10,000 students.

Voting rights experts agree that the proportion of Georgia voters who are affected by the provision ultimately only makes up a small portion of the state’s electorate.

However, they also note that any impact the law has might affect the outcome of any close race given how tight important elections in the state have been over the past two election cycles.

The relevant clause was included in the state’s voter ID statute from 2006. Despite numerous amendments, the law still mandates that voters must show a driver’s license from Georgia, a license or identification card from another state, a voter identification card from Georgia, a passport, a card for a military member or tribal member, or any other identification card issued by a branch, department, agency, or other organization of the state of Georgia to cast a ballot.

Public colleges and universities fall under that last group, but not private ones.

“Take a look at any recent Georgia election and you’ll see that every vote letters to the outcome there right now. The margins are exceptionally thin,” Danielle Lang, the senior director of the voting rights unit at the Campaign Legal Center stated. “So, in a race like this, making sure that access is as broad as possible is essential to make sure the results reflect the desire of Georgia voters.”

The clause is absent from Georgia Election Law SB 202, which was passed in 2021 and added several new regulations and limits on voting.

The voter’s driver’s license number or another form of official identification must be included with the application and ballot when casting a mail-in ballot, according to SB 202. Private college and university students in Georgia who voted by mail in 2022 would have needed to include a different form of identification with their application and ballot.

“This [provision] isn’t even part of SB 202, but all of these laws kind of interact with each other and have a cumulative impact, so when you stack them up, they often end up having a noticeable disenfranchising effect in the broader picture,” Garabadu of the Georgia ACLU said.

Garabadu also pointed out that several states, including Wisconsin and Alabama, had either changed their voter identification laws or provided new guidelines on how to interpret them to accept school IDs from private schools and universities as a valid form of identification while voting.

Groups like Vote Riders put boots on the ground in the months before the general election to prepare students who might have otherwise unexpectedly confronted the rule at a polling location.

The group has continued to be active in the weeks since, working to ensure that students, particularly at private HBCUs, who are already registered voters, are aware of the identification they must bring if they cast a ballot in person in the Senate runoff on Tuesday.

They are also reminded that they can request a provisional ballot if problems arise. Garabadu observed that several states, including Wisconsin and Alabama, had either updated their voter identification statutes or provided new instructions on how to interpret them to recognize private college and university school IDs as a valid form of identification.

“You have a lot of students who came from cities like Philadelphia, or New York and they never needed a driver’s license or had a state ID in their state,” Sylvester Johnson, an Atlanta-area organizer stated.

He noted that the only form of photo ID some he’d talked with on various Atlanta campuses currently had been their student ID from the private HBCU they were enrolled in.

“These are the kind of students who are affected,” he said.