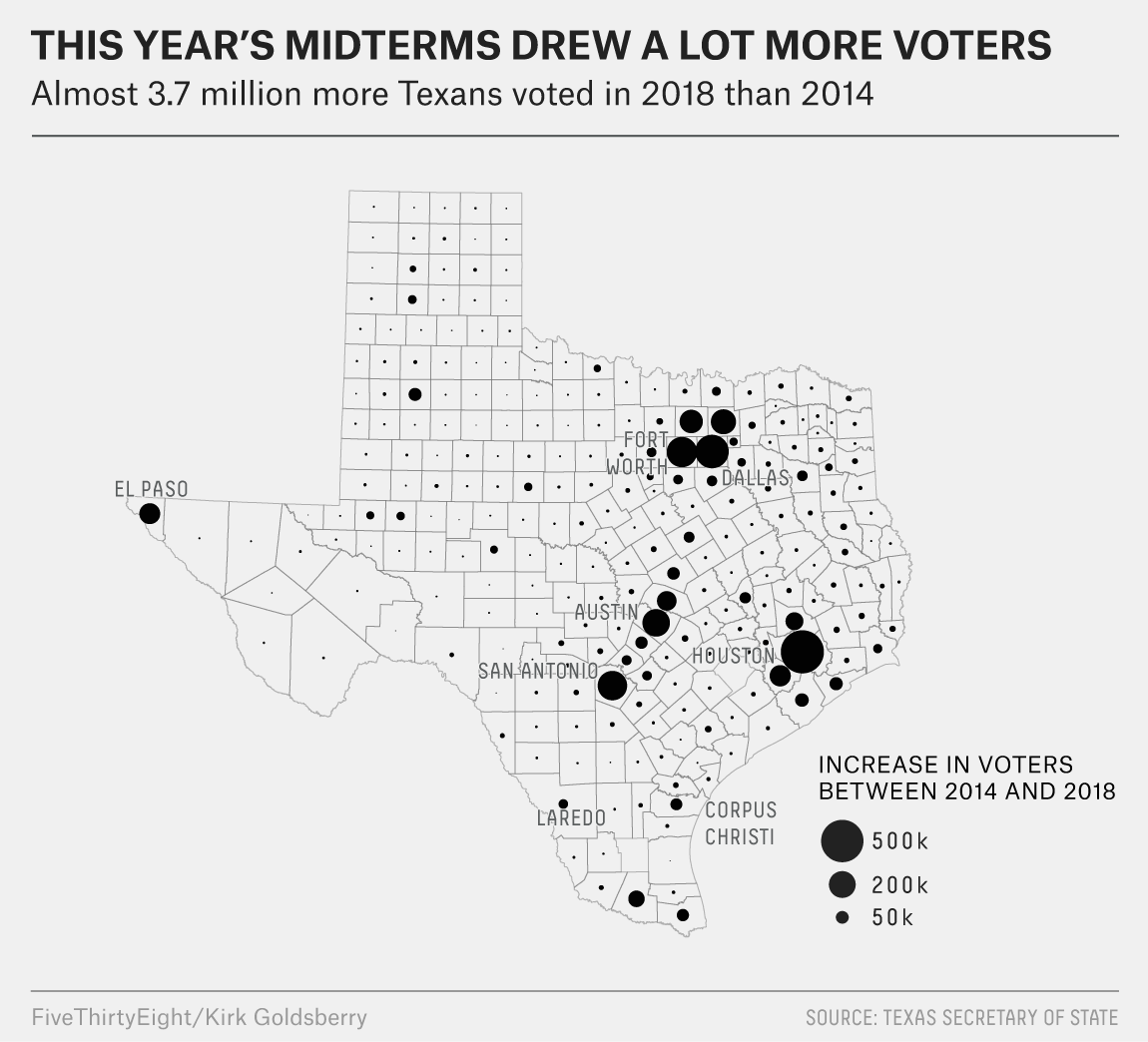

Over 8.3 million Texans voted in the 2018 midterm elections. It’s an astounding figure, especially considering that about 4.6 million voted in the midterms just four years ago. That difference — almost 3.7 million — says a lot about the changing face of the Lone Star State, but Tuesday’s result says more. Yes, Texas is growing, but as of 2018, it’s still red and still likes Ted.

But let’s back up for a moment. The Democratic Senate candidate in Texas, Rep. Beto O’Rourke, came within 3 percentage points of defeating Sen. Ted Cruz, which is close enough to put Texas at the center of two of the big post-election questions: Is Texas a swing state? And will O’Rourke run for president?

So what really happened in Texas? Let’s start with the basics:

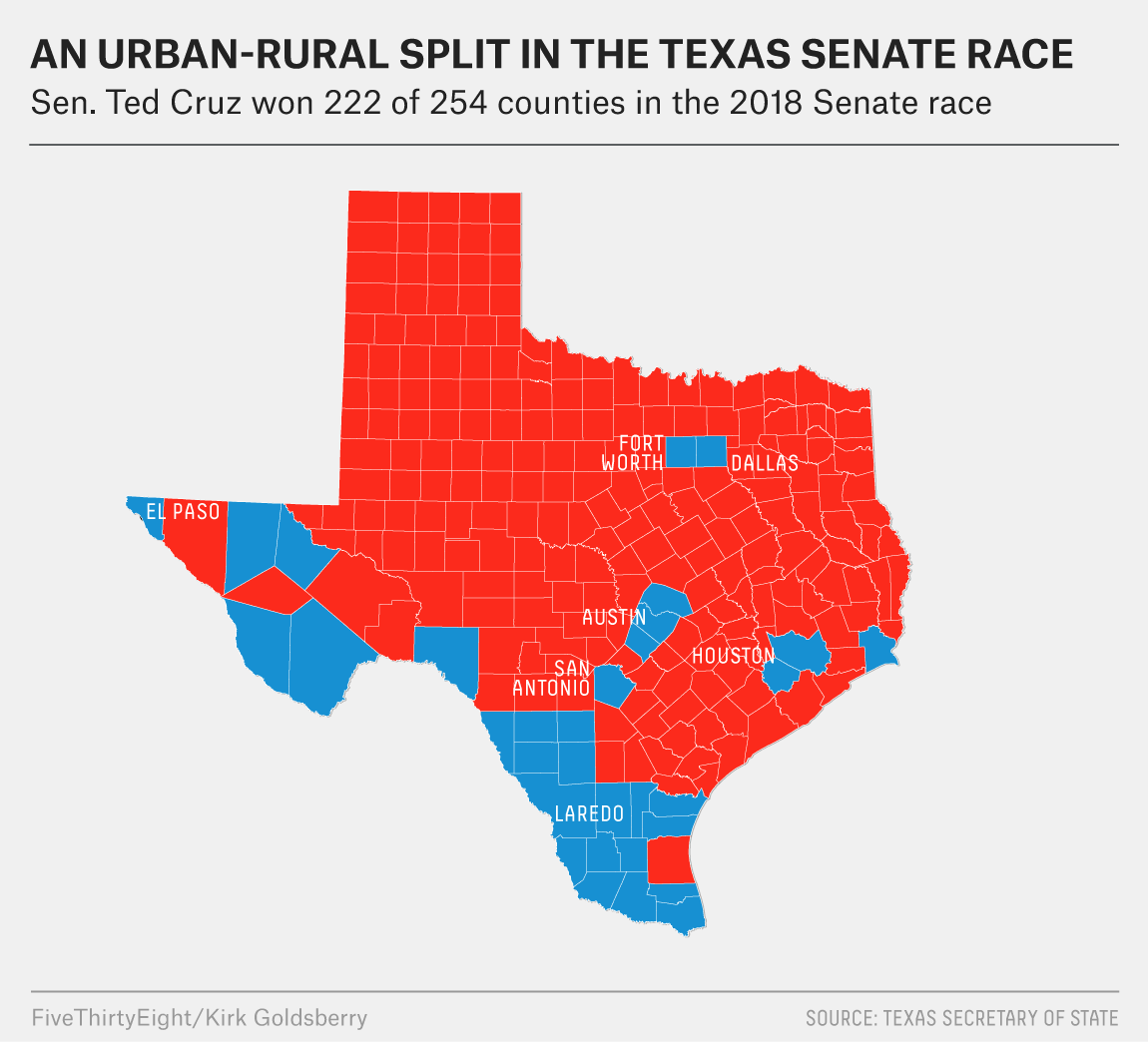

The 2018 result took a familiar form, with Democrats winning in the cities and in South Texas, and Republicans winning everywhere else. But this basic map fails to reveal key changes that are shifting the electoral math in Texas.

As Democrats yearn to make Texas a swing state in 2020, they will be helped by major population growth in and around the state’s cities. The rising population of these metro areas combined with record turnout for a midterm, changed the electoral balance of the state in 2018 and may continue to shift it in the next few years.

Almost all of that new voting power came from in and around the state’s four big cities: Houston, Dallas, Austin and San Antonio.

Cruz beat O’Rourke by a margin of about 220,000 votes. It was a gratifying victory for Cruz and Republicans after Democrats had poured so many resources into the race, but it was also closer than many expected. By grabbing 48.3 percent of the vote, O’Rourke performed better than any Democrat had in a statewide race in Texas in a long time. Even though he won just 32 of the state’s 254 counties, O’Rourke’s margins within the state’s booming metro areas suggest that those parts of the state may be getting even more Democratic.

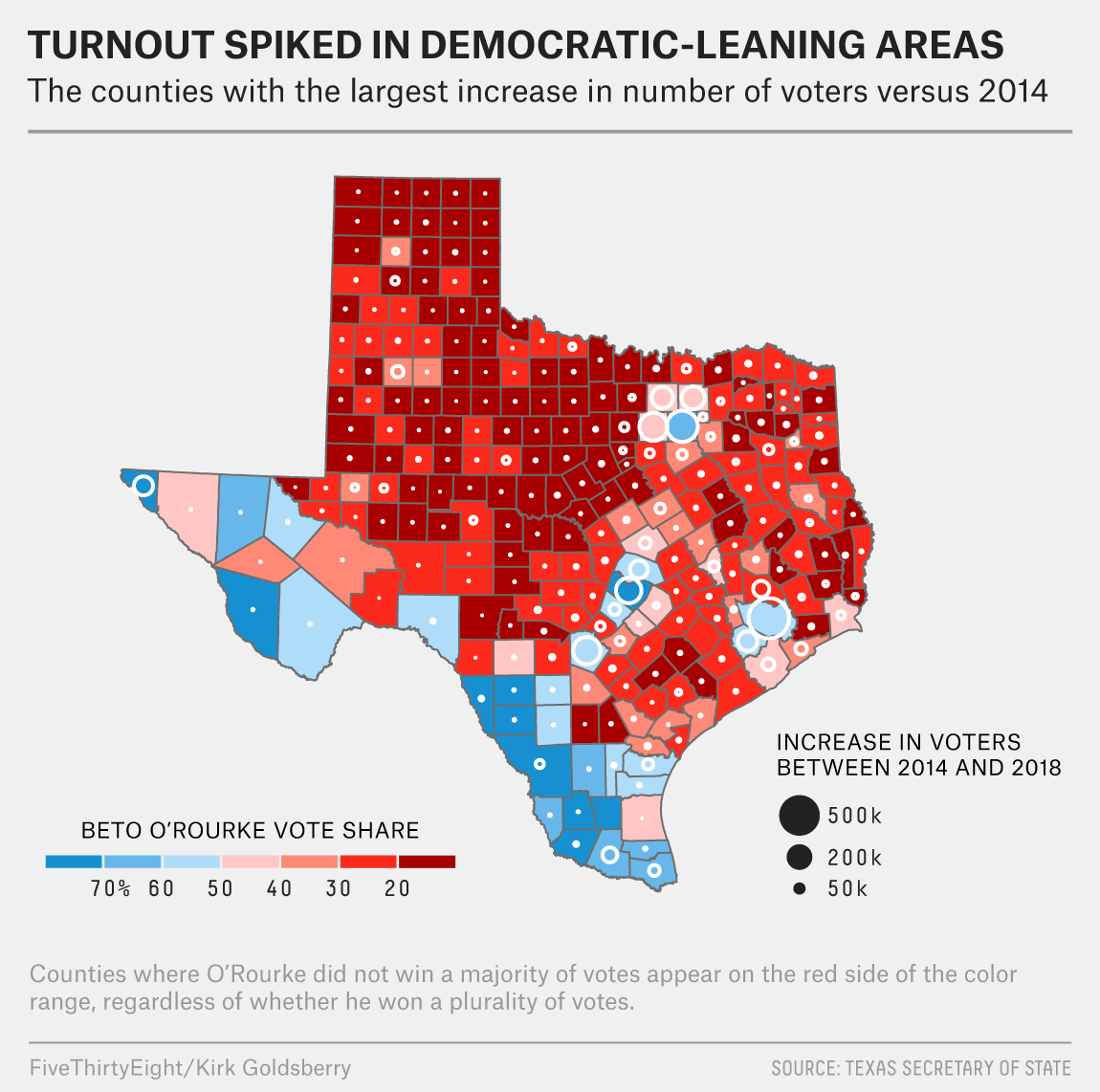

Not only did O’Rourke dominate Cruz in the state’s five most-populous counties, encompassing the urban cores of Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, Austin and San Antonio, he also won a higher percentage of the vote there than Hillary Clinton did, suggesting that O’Rourke was a more effective candidate in these key zones than Clinton was. In future races, Democrats would be thrilled if their candidates can re-create O’Rourke’s margins, but if they regress to Clinton’s margins, it’s hard to see a blue Texas anytime soon.

O’Rourke outpaced Clinton in key counties

All votes cast in Texas’s five biggest counties and vote shares for Beto O’Rourke in 2018 and Hillary Clinton in 2016

| 2018 | 2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County | Total votes | O’Rourke’s vote share | Total votes | Clinton’s vote share |

| Harris | 1,205,394 | 58.0% | 1,312,112 | 54.0% |

| Dallas | 723,755 | 66.1 | 758,973 | 60.8 |

| Tarrant | 626,280 | 49.9 | 668,514 | 43.1 |

| Bexar | 546,107 | 59.5 | 589,645 | 54.2 |

| Travis | 480,705 | 74.3 | 468,720 | 65.8 |

| Total | 3,582,241 | 60.6 | 3,797,964 | 54.9 |

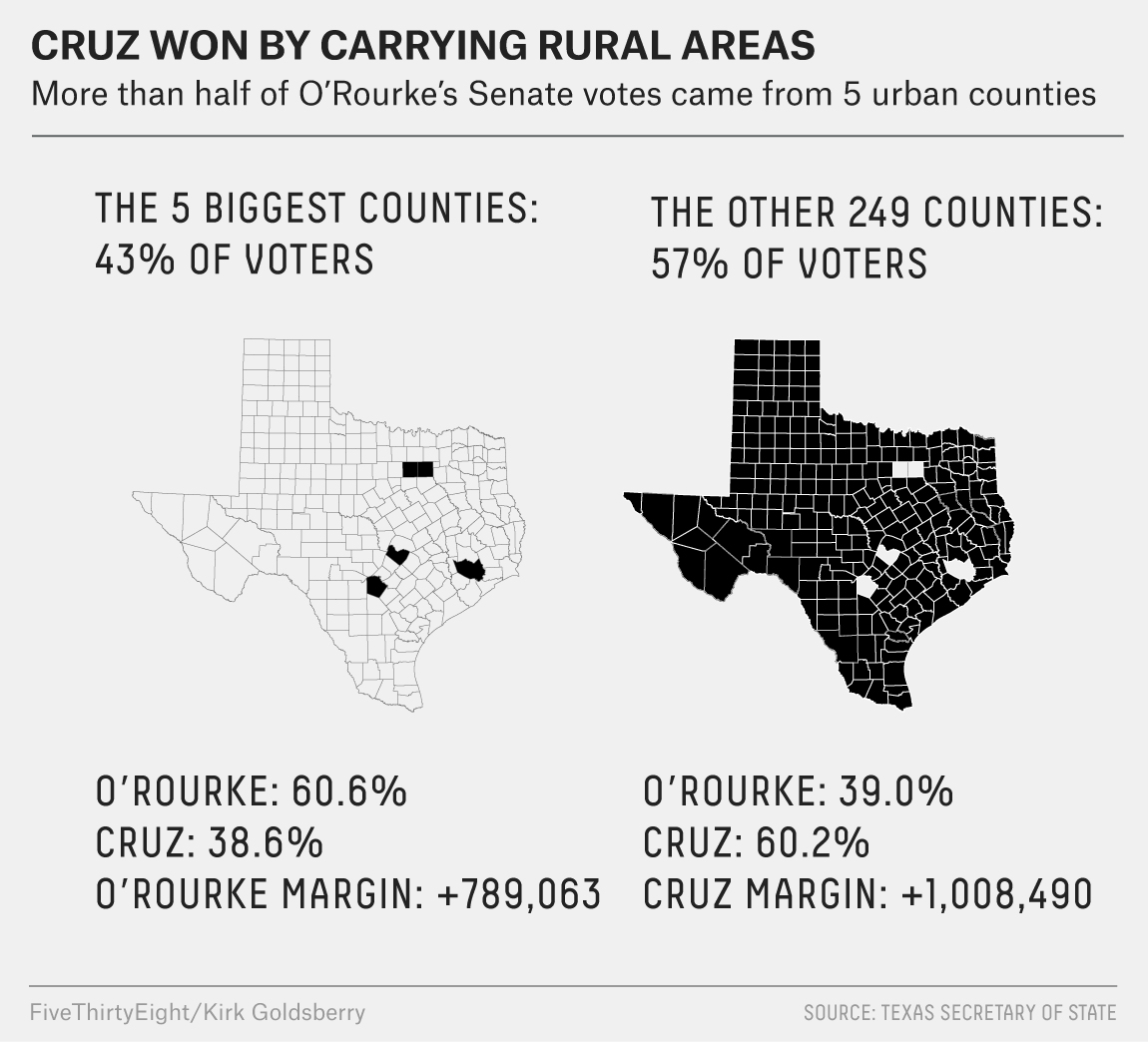

A whopping 43 percent of all votes cast in Texas in 2018 came from these five urban counties. They represent the key to any Democratic hope in this state, and they are only becoming more significant; O’Rourke had to win big in these counties to have any shot at victory, and he did, taking 60.6 percent of the vote and putting himself almost 800,000 votes ahead of Cruz. For comparison, Hillary Clinton won 54.9 percent of the vote in these big counties and outpaced President Trump there by only about 563,000 votes.

But although O’Rourke did well in those urban counties, Cruz did even better everywhere else, and that was the key to his victory. Cruz churned up enough non-urban support to more than compensate for the major losses he took in cities. More than a third (34.5 percent) of the votes Texas cast in the state in 2018 came from relatively small counties that tallied fewer than 100,000 votes each. And in these areas, Cruz excelled, chalking up over 67 percent of the vote and amassing a vote margin of more than 1 million.

The geographic structure of the 2018 result shows where the battle lines will be drawn in the future. Democrats haven’t done well in rural areas, either this year or in the recent past, so they probably shouldn’t pin their hopes on better performances by their candidates in those areas. But they could continue to build their already-large advantage in urban areas: Democrats hoping to turn this state blue need the state’s urban areas to claim even more voting power, either through population growth, increased turnout, or a combination of both

Cruz won by 220,000 votes last week. But in Harris County alone, 500,000 more people voted in the 2018 midterms than had voted in 2014. In Dallas County, 300,000 more people voted than in the last midterms, and in Travis, Bexar and Tarrant counties, 200,000 more people voted.

Indeed, aside from some noteworthy increase in voter numbers in suburban Dallas, the biggest white circles on the map above tend to hover over Beto country. Meanwhile, the darkest red counties — the places that carried Cruz back to Washington — have exhibited very little, if any, change in the number of votes cast compared to 2014. Those areas may be staunchly red, but they’re also staunchly stagnant too. O’Rourke almost won in 2018 by taking roughly 60 percent of the vote in the big five counties. This map suggests that if Democrats can repeat that feat as these places continue to grow, that may be all they need to turn Texas blue.

The Texan electorate could approach 10 million voters in 2020. Sen. John Cornyn’s seat will be up that year, and if he seeks re-election, which seems likely, he’ll do so in a wildly different environment than the one he won in back in 2014, when he received 2.9 million votes. Tuesday taught us there are at least 4.2 million Cruz voters in Texas. That’s incredible, but even those 4.2 million votes may not be enough to get it done in 2020. It could take 5 million votes or more to win the Senate seat here in 2020. One thing is for sure, however: Neither party can get to numbers without playing reasonably well in those big five counties.

Still, maybe half the story in Texas last week was about the long-term demographic trends in the state — the other half was about O’Rourke. If Democrats can repeat the turnout levels and urban-rural splits O’Rourke achieved here this year, the swelling metropolitan electorate may do the rest. Everything’s getting bigger in Texas, especially the cities. But that’s a big if.