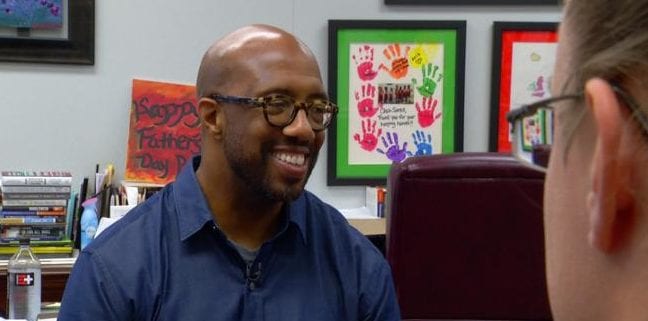

An interview with Michael Sorrell, president of Paul Quinn College and one of Fortune magazine’s 2018 World Leaders

When Michael Sorrell agreed to a controversial decision to disband the football program at Paul Quinn College in 2007, he saw it as the only way to save the financially troubled historically black college. Located in a working-class African-American neighborhood in south Dallas, Paul Quinn was on the verge of shuttering unless Sorrell, a relative novice in higher education, somehow came up with a miracle.

Paul Quinn was founded in 1872 and was the first institution of higher learning for African-Americans west of the Mississippi River. But as enrollment plunged from 1,000 to 150 students and annual deficits soared to as high as $1 million a year a decade ago, the school devolved into an eyesore, with several buildings in disrepair while others sat vacant.

No one wanted to be the president of Paul Quinn, which is why Sorrell, a Dallas-based attorney with no experience in higher education, initially accepted the job on a 90-day contingency basis as the board of trustees searched for a full-time president. Sorrell, who was part of a group in negotiations to purchase the NBA’s Memphis Grizzlies and name him team president, awaited his fate. When the deal to acquire the Grizzlies fell through, Sorrell became Paul Quinn’s permanent president.

His idea to terminate the football program and convert the field into the state-of-the-art WE Over Me Farm where students can work, and from which food is donated to the surrounding community and sold to area businesses for profit, was born out of Sorrell’s desperation and innovation. It worked because Sorrell convinced everyone, including himself, that it couldn’t fail.

Paul Quinn, which was once on the verge of bankruptcy and de-accreditation, has seen its enrollment increase to more than 550 students today, and the graduation rate for students enrolling in 2006 and 2009 improved from 1 percent to 13 percent. In August, the school broke ground on a 40,000-square-foot educational and residential building made possible with $7 million in donations — the school’s first new building in 40 years. Paul Quinn now operates at a profit and has received the most seven-figure gifts in school history while securing full accreditation from the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools.

“I took some criticism, but we couldn’t afford football,” Sorrell told The Undefeated. “The dominant reason for us terminating the football program was economic. But another reason was maybe there’s more than one way out of poverty for young black men. Maybe your mind will sustain your climb out of poverty more than your body.”

A lunch meeting with Dallas businessman and environmentalist Trammell S. Crow prompted Sorrell to reveal there wasn’t a single grocery store for miles to accommodate the community surrounding Paul Quinn. Crow inquired about the feasibility of an on-campus garden. Sorrell suggested the football field, which had been unused for two years.

“He said, ‘Can you do that?’ I said, ‘I’m the president,’ ” Sorrell said. “So he gave some money to turn 30 yards of the football field into a community garden. He also gave money so we could open up a community garden at the church across from the school.” Crow later connected Paul Quinn with Pepsi Co., which also contributed financially to the farm. In 2014, Crow provided the largest gift in school history, $4.4 million, and has become so influential that the new building will be named after him.

“We didn’t know anything about farming,” Sorrell said. “We were inexperienced, but we had righteous rage and we were unafraid to fail. True failure would have been never trying to improve the condition of people in this community, and we thought that was wrong.”

Students at Paul Quinn College at the football field turned farm.

Courtesy of KSJD Radio

As of August, the WE Over Me Farm has grown more than 60,000 pounds of produce and features a 3,000-square-foot greenhouse. Some of the produce is consumed in the dining halls. It’s also sold to Dallas restaurants and grocery stores. The school’s largest customer, Legends Hospitality, serves AT&T Stadium, home of the Dallas Cowboys. In 2015, Paul Quinn hired a farm director who specializes in organic farming and opened a farmers market that brings together 10 to 12 vendors each week. Popular items include collards, mustard greens, cabbage, lettuce, carrots, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, garlic, okra, cucumbers, corn, peas, watermelon, cantaloupe, pumpkins and squash.

“It saved our school in one regard because it changed the narrative,” Sorrell said. “No longer were you going to talk about Paul Quinn from the perspective of a need institution that did not have what it needed and should be pitied. When you are in a crisis, you have to change the narrative, and that’s what it allowed us to do. It gave people a reason to look at us and see hope. It’s one thing for me to go around giving speeches about believing and hope and we’re going to accomplish things. It’s something entirely different to give people tangible proof of hope. And from that moment forward, we began to exceed people’s expectations.”

Speaking at the prestigious SXSW EDU Conference & Festival in March in Austin, Texas, Sorrell emphasized that what works at Paul Quinn won’t necessarily yield similar results at schools with greater resources. For instance, cutting football wasn’t the only way to go. But it was considered the best way among other options.

“When I was a young college president, I was stressed out,” said Sorrell, who was named one of Fortune magazine’s 2018 World Leaders, one of only two college presidents to receive the honor. “I had just turned 40. I was frustrated. I was in charge of a school that was failing and there was no guarantee this was going to work. I faced a very real possibility that Paul Quinn College could have survived Reconstruction, it could have survived Jim Crow but it couldn’t survive my presidency. That scared the daylights out of me. At Paul Quinn, people look at our students and dismiss them. Eighty to 90 percent of our students are Pell Grant-eligible. Our average ACT score is 17. So what? That’s just numbers on a page. Maybe the problem isn’t that you couldn’t learn. Maybe the problem is that people couldn’t teach you.

“There was no path forward for us simply doing what other schools did because they were doing it longer and better. That wasn’t going to work for us. We weren’t that type of institution. We didn’t have those type of resources. Our way forward was going to have to be something different. And that different for us was turning the institution around and saying if we were going to design a university for today’s students, what would that look like? If we were going to demand our place in higher education, how would we break down the doors? We were going to have to be less of a college and more of a movement.”

The WE Over Me Farm was only the beginning. In 2013, Paul Quinn experimented with an urban work college in which all students are required to work at jobs on campus and later off campus for potential employers. Students have $2,400 of their wages go toward their tuition and keep the rest. In 2017, Paul Quinn was designated by the U.S. Department of Education as the ninth federally recognized and the first historically black work college.

“What’s truly amazing about what Paul Quinn has become is this idea that we created our own system of higher education,” Sorrell said. “We lost 80 percent of our student population in my first two years. We’re now over 550. We’ve had to manage that growth because we didn’t have [sufficient] housing. There were no urban work colleges [before Paul Quinn]. That model did not exist. If you live on campus, all of our residential students have a job. They work an average of 15, 16 hours per week. They work on and off campus. They have work transcripts so they can show what they can do, and they have their academic transcripts to show what they learned. We also reduced tuition and fees and made it easier for students to graduate with less than $10,000 in student loan debt. We have taken aim at what we have felt are the most dominant issues of our day and are working to solve them.”

In July, Paul Quinn announced that the inaugural site of its urban work college network will be in Plano, a Dallas suburb. Thirty-three students will live in apartments the first year, and corporate sponsors will provide paid internships and classroom space.

“We want to open Paul Quinn global campuses and urban work colleges all over the world,” Sorrell said. “Plano was our expansion model. This is about identifying your competitive advantage. We’re in one of the strongest, most thriving business centers in the country. Why wouldn’t we craft a way that allowed us to take full advantage simply of what we have in our midst?

“The farm was just the tip of the iceberg. That gave people the first example of us being able to do things that people weren’t doing or hadn’t done. We’ll use what we have to serve our institution and the community we serve. We give away close to 15 percent of everything we grow. Our largest customer is the Dallas Cowboys because, you know, we still run a business here. But, quite candidly, the farm is wonderful, but the farm isn’t what makes us special.

“I’ll tell you what I tell everybody: We are just warming up,” Sorrell said. “We haven’t even taken our best stuff off the shelf yet. We’re not saying our way is the only way or the best way. We’re saying what we believe yields the best results for the community we serve.”