With the final polls finished, the last ads cut and well over 35 million people already having voted, political operatives in both parties expect Democrats to win back control of the House on Tuesday and make significant gains in state capitals even as Republicans keep narrow control of the Senate.

But as President Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 showed, upsets do happen. And in this election, several factors exist that could change the expected results — in either direction.

Among the big question marks:

How badly will Democrats lose among blue-collar white voters, the group that forms the base of Trump’s support?

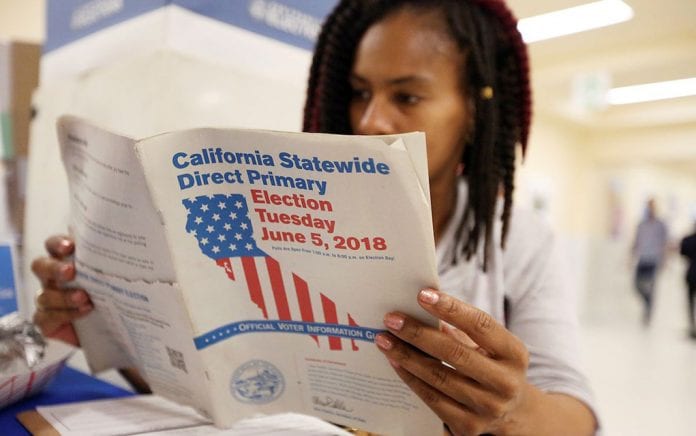

What will turnout look like among Latinos, who are key to Democratic hopes to win Senate seats in Arizona, Nevada and several House seats in California and elsewhere in the Southwest?

“The question is have we engaged the Latino community enough to generate turnout?” said Democratic pollster Mark Mellman. “It’s going to vary from place to place.”

And in an election where partisans on both sides seem fired up to vote — witness the early voting that has broken records in many states — how will those with weaker partisan ties divide?

About four in 10 partisans on each side said they were closely following the election campaign, according to the final University of Southern California-Dornsife-Los Angeles Times poll.

That’s a big shift from 2010, when the Republicans won the House majority that they’ve held for the last eight years. In the run-up to that election, a lot more Republicans than Democrats took an interest in the campaign, and that correctly forecast a poor Democratic turnout. Four years before that, it was Republicans who were demoralized and Democrats who took the most interest, leading to a Democratic wave.

Earlier this year, Republican strategists worried that Democrats once again had the sort of enthusiasm edge they enjoyed in 2006. But in the closing weeks of this campaign, that concern has diminished.

“It’s clear that, in most places, Republicans have solved our September enthusiasm problem,” Glen Bolger of Public Opinion Strategies, a leading Republican polling firm, said on Twitter earlier this week.

But that cleared up only one of the big problems the Republicans face, he noted.

“What’s not clear is whether we’ve solved our problem with independent voters,” he said. “That will be the difference between winning and losing in close races.”

The USC/Times poll found self-described independents favoring Democratic control of Congress this year by 62 percent-38 percent.

Overwhelmingly, that’s because the election has turned into a referendum on Trump.

“The central issue is him,” said Robert Shrum, the co-director of USC’s Center for the Political Future, which co-sponsored the poll. “He’s not managed to substitute” other issues.

The poll found about one in four voters saying that their views of Trump outweighed their views of the individual candidates. Among those with that view, Trump’s opponents outnumbered supporters by roughly 3-2.

Trump’s political approach has never been to win over detractors. Instead, he has sought to boost turnout among supporters. In the campaign’s final weeks, his main approach has been to pound away at what he describes as the threat to security from immigrant caravans moving north through Mexico and Central America.

Republicans hope that approach may pull their candidates to victory in a few key Senate races and help, as well, in House races, especially in more conservative areas.

There’s precedent. In 2004, strategists for President George W. Bush correctly predicted that he would do well in his re-election campaign by emphasizing a tough response to the threat of international terrorism. Women, in particular, would respond to Bush’s argument, they argued, and “security moms” became a mantra for the Republican campaign.

In his final rallies this time, Trump has said much the same.

“Border security is very much a woman’s issue,” he said during a rally in Montana on Saturday. “Women want security,” he said. “They don’t want that caravan.”

Of course, Bush’s campaign came in the aftermath of a devastating terrorist attack that killed more than 2,700 Americans.

By contrast, the caravan Trump has inveighed against consists of a few thousand people, including many women and children, who remain hundreds of miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

In the poll, about one in six voters said they saw the caravan as “potential terrorists who should be turned away as a threat to the United States.” That share rose to about one in three among those who said they would vote for a Republican for Congress this year.

Many more, however, about four in 10 voters, said they saw the caravan as mostly “asylum seekers in need of humanitarian assistance,” while about three in 10 said they thought the group was likely a mix.

Another contrast between Bush’s approach and Trump’s could prove key: Bush coupled tough talk about a “global war on terror” with exhortations against religious prejudice. Trump almost never makes such appeals. Instead, he denounces perceived enemies, including parts of the news media whom he has dubbed “enemies of the people.”

By roughly a 3-2 margin, voters said they saw such comments by Trump as “dangerous language that could incite violence.” Independents took that view by 2-1, the poll found.

As violent attacks punctuated the closing weeks of the campaign, polls have found signs of movement against the Republicans in a number of races.

The backlash against Trump carries the biggest political punch in suburban areas. There, anger toward the president from minorities and college-educated whites, especially women, has endangered dozens of Republican candidates and once-reliably Republican districts from Orange County, Calif., to the outskirts of Philadelphia and New York have turned into electoral battlegrounds.

But the resistance to Trump has failed to enlist most non-college white voters. Their support has kept Republicans in the fight in more blue-collar congressional districts from northern Los Angeles County, where Republican Rep. Steve Knight and his Democratic challenger, Katie Hill, have been locked in a tight contest, to downstate Maine, where a similarly close fight pits first-term Republican Rep. Bruce Poliquin against his Democratic challenger, Jared Golden.

The USC-Times poll shows near perfect symmetry between the two groups of white voters: Those with college degrees side with the Democrats by nearly 2-1, while those without side with Republicans by an identical margin.

Those figures, however, represent an average of voters from across the country. The breakdowns in individual districts vary widely.

In the most contested districts, whites without a college education will end up on the Republican side, “but by how much, that’s the question,” said Mellman, the longtime Democratic pollster.

“The margin by which we lose them will make a lot of difference in many races.”

While Trump has emphasized security from outside threats, Democrats have campaigned consistently on security of a different sort — protection against the threat of ruinous medical bills. They have saturated the airwaves with advertisements highlighting Republican votes to end insurance protections for people with pre-existing medical problems.

Almost one in five voters listed health care as the most important issue in the election, up several points from September, when the poll last asked voters to rank issues. The share listing health care as the top issue outnumbered those listing illegal immigration by roughly 3-1.

Republicans have insisted that they, too, want to protect people, but they have not gained much traction.

By 55 percent-31 percent, likely voters said they trusted Democrats more to protect people with pre-existing health conditions.

Even a significant share of Republican voters expressed doubts about their party on that issue. While 91 percent of Democratic voters said they trusted Democrats more on the issue, only 72 percent of Republicans said they trusted their party more. About one in five Republican voters said they weren’t sure.

Overall, the poll, which has tracked voters over the last several weeks, shows Democrats ahead by 15 percentage points, 56 percent-41 percent, when those most likely to vote said which party’s candidates they either had voted for already or expected to vote for this year.

A second measure, which factors in voters’ estimates of how likely they are to vote, puts the Democratic lead at 10 percentage points, 52 percent-42 percent.

That so-called probabilistic measure should, in theory, offer a better forecast because it takes into account information from all voters, not just those deemed most likely to vote. The probabilistic measure weights voters according to how likely they say they are to vote: A person who is 50 percent likely to vote, for example, has half as much impact on the outcome as one who is 100 percent likely. The poll is testing both approaches to see which most accurately forecasts the actual vote, said survey director Jill Darling.

Other polls released Sunday forecast similar results. The NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, for example, pegged the Democratic advantage at 7 points, 50 percent-43 percent, while the ABC/Washington Post survey found Democrats with a 51 percent-44 percent lead among likely voters.

The USC-Times poll, overseen by Darling, was conducted Oct. 28-Nov. 3 among 3,936 adult Americans, including 3,499 registered voters of whom 2,521 were considered likely to vote and 1,091 already voted.

Respondents were drawn from a probability-based panel maintained by USC’s Center for Economic and Social Research for its Understanding America Study. Responses were weighted to accurately reflect known demographics of the U.S. population. The margin of error is 2 percentage points in either direction. A full description of the methodology, poll questions and data, and additional information about the poll are posted on the USC website.

The post Polls Point to Democratic Takeover of the House, but Here’s What Could Change That appeared first on The Network Journal.