By Shelby Stewart ·Updated September 1, 2023

By Shelby Stewart ·Updated September 1, 2023

Last week Time Of Essence showcased how the decade of the 1980s was marked by economic upheaval, and yet, Black women were still taking up space. That carried over into the 90s as well, and there was an authority in Black women voices. The magazine was a reflection of that—covering everything from the AIDS epidemic to sexuality.

The 90s marked the 20th anniversary for the magazine, a proud moment for ESSENCE at the time. By then, Bill Clinton had been elected as president in 1992, what ESSENCE President and CEO Caroline Wanga called “the first Black president.” Clinton marked a progressive era for Black people, and Black women in particular.

The decade included a Black Miss USA, Carol Gist, Mae Carol Jemison, the first Black woman to take a trip to space, and Carol Mosley Braun, the first Black woman elected to the senate. From here, art imitated life, giving birth to very rich Black media narratives such as Living Single, Moesha, and even films like Sister Act and A Thin Line Between Love and Hate. “You’re starting to see the depth and breadth of Black, and the star power that comes with that, and so we start to see the era ofthe ESSENCE cover becoming a place of the Black celebrity,” Wanga said.

Before Black award shows were around to celebrate Black excellence, ESSENCE sat in that void through various mediums. Enter the 1994 ESSENCE Awards, one of the first Black award shows. The show read like a who’s who of Black Hollywood, with the likes of Spike Lee, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman, and Michael Jackson in the audience, as well as Sinbad and Vanessa Williams as hosts of the cultural affair.

Elsewhere in 1991, Clarence Thomas was accused of sexual misconduct by Anita Hill, at a time where he was being considered for Thurgood Marshall’s seat on the supreme court. According to Taylor, Hill “bravely gave voice” to the sexual conduct most Black women had once encountered. Something that former ESSENCE employee, Hariette Cole was all too familiar with. “I love ESSENCE,” Cole said. “Unfortunately, I didn’t always feel safe.” ESSENCE president Clarence Smith sexually harassed Cole, disclosing that he wanted her to come and model for him in his home in a red bikini and pumps. Smith would tell Cole that “this is how you succeed in business.” The event would eventually lead to Cole leaving ESSENCE in 1995.

In the 90s, Blak love was prospering, however, the aesthetic of Black love was primarily heterosexual, leaving little room for other relationship dynamics. It wasn’t until then-executive editor Linda Villarosa confessed to Taylor that she was a lesbian, that the narrative changed. In the May 1991 issue of ESSENCE, the focus was on Mother’s Day, and Taylor’s editorial decision to place a focus on mother-daughter pairs, ended up highlighting Villarosa and her mother, Clara. The article received positive feedback from readers thanking them for sharing their story.

Taylor’s ideas continued to be a disrupter telling stories of a Black women, which led to the August 1998 cover, with Isis Sapp-Grant, a gang member of the Deceptinettes, a girl gang in New York City, and sister gang to the Decepticons. The cover story provided insight into women’s gang violence, a story that hadn’t yet been told.

The same would happen with Rae Lewis Thorton, a Black woman living with AIDS, who was able to tell her story in the pages of ESSENCE in December 1994. Her story helped to break down the stereotypes of what HIV/AIDS was, and how the virus was adversely impacting Black women at the time.

May 1995 marked ESSENCE’s 25th anniversary, and Lewis had big plans. In conversation with jazz musician George Wein, he created what would become the ESSENCE Festival of Culture. Lewis’ partner Smith, and EIC Taylor weren’t fully onboard, so it wasn’t until Taylor created a free space for Black women to convene during the music festival that the idea truly began to take shape. The inaugural year of the festival proved to be successful, and Lewis wanted to make the celebration annual, however politics would become an obstacle in making it happen.

The change of power in the state would lead the next governor of Lousiana, Mike Foster, to rid the state of all affirmative action programs. Because Lewis was a believer in affirmative action, he made the decision to not bring the festival back to Louisiana. It wasn’t he got a call from Lieutenant Governor, Kathleen Blanco, asking him to sit down with the governor. After hearing Ed’s story, Foster lifted the affirmative action ban, which brought the EFOC back to the Big Easy. Today, the festival is the nation’s largest festival by per day attendance. The festival is also a larger driver of revenue for the ESSENCE brand.

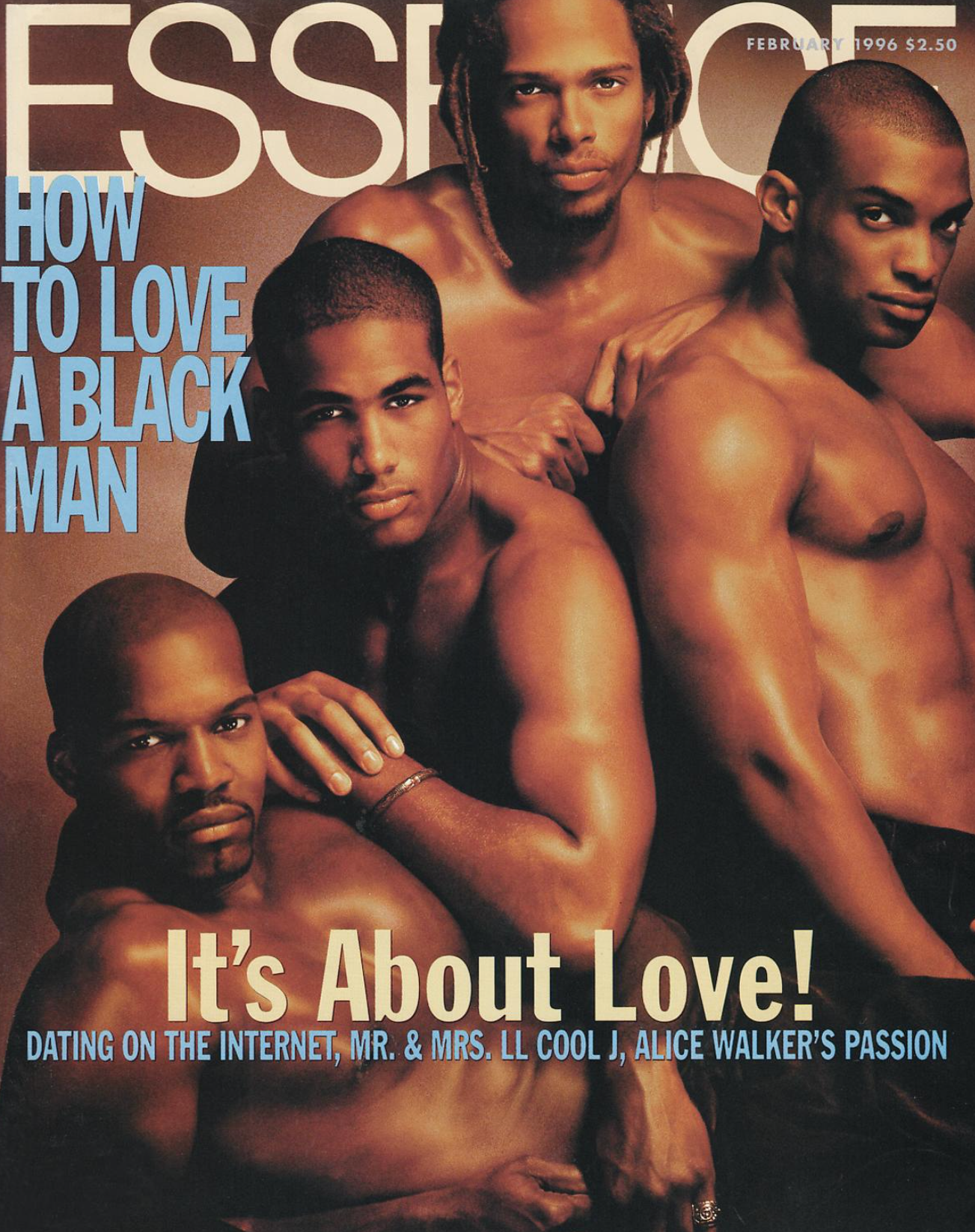

February 1996 cover of ESSENCE

February 1996 cover of ESSENCE

While the magazine showcased Black women of all creeds and colors, it was the Black men who stole the show on the covers, (and sold a lot of issues). It was the February 1996 cover with Boris Kodjoe, and Taylor Alexander that became one of the magazine’s most sold issues. Mikki Taylor says that the ESSENCE’s subscriber base grew to be 25 percent male at the time.

Nonetheless, an area where the magazine also saw revenue was in advertising, but advertisers were largely selling ads for cigarettes and alcohol, with the impression that Black women were partaking more, a notion that was drastically untrue. In the 90s ESSENCE made a change, with the help of Mikki Taylor. The team created Smart Beauty. “We had to teach the industry how to reach Black women in beauty,” she said. Exposing Black women to the beauty industry is what would make the change in ad revenue, increasing to “a half million dollars for a page.”

ESSENCE would see exponential growth in the mid 90s, however, competition would also grow. As Black women would permeate mainstream media, the legacy magazine wouldn’t be the only editorial placing Black women on the cover. As hip-hop was growing, it was creating space for women rappers such as Lil Kim and Lauryn Hill to be on the cover of magazines such as VIBE and Ebony.

ESSENCE was reluctant to accept hip-hop, primarily because of Lewis and his beliefs—”I couldn’t relate,” he said. “The kinds of things they were saying about Black women. Bitches and hoes, it was just not acceptable.” Many would assume that Ebony was ESSENCE’s main competitor, however, the Quincy Jones-backed VIBE was a larger contender, mostly because of the cultural cover stars that would place the likes of Mary J. Blige and Queen Latifah on its cover. Honey, which would make its debut in 1997, would also become what Jamilah Lemieux called, “a young woman’s ESSENCE.”

The magazine still managed to prevail. While the VIBEs would cover solely music, ESSENCE was all encompassing, and though reluctant to pick up on hip-hop and the misogyny that came with it, the magazine shifted its focus to another big issue at the time, apartheid. Nelson Mandela being released from prison after 20 years was major news, and something ESSENCE was at the forefront of.

However, the reluctance to embrace hip-hop wouldn’t last long—Lewis’ business acumen was the impetus of his interest, and the 25th anniversary ESSENCE Awards, Salt-N-Pepa were on the bill to perform. Lewis’ hip-hop endeavors wouldn’t stop there either, he had intentions to acquire VIBE. Yet, in a conversation with Gerald Levin, the former CEO of Time Inc., changed their trajectory—Levin was interested in investing in the publication.

Next week on Time Of Essence, tune in to see how the new millennium fared for ESSENCE.

TOPICS: 90s Time of Essence

The post Recapping ‘Time Of Essence’ Episode 3: The 1990s appeared first on Essence.