*As we celebrate the 45th anniversary of Black Music Month, we are reminded of the rich tradition of our music and culture. Black Music Month was founded by Kenny Gamble, Grammy Award-winning producer and songwriter and one of the founders of Philadelphia International Records; along with co-founder Dyana Williams, award-winning radio and television broadcaster; and co-founder Ed Wright, Cleveland’s legendary radio broadcaster.

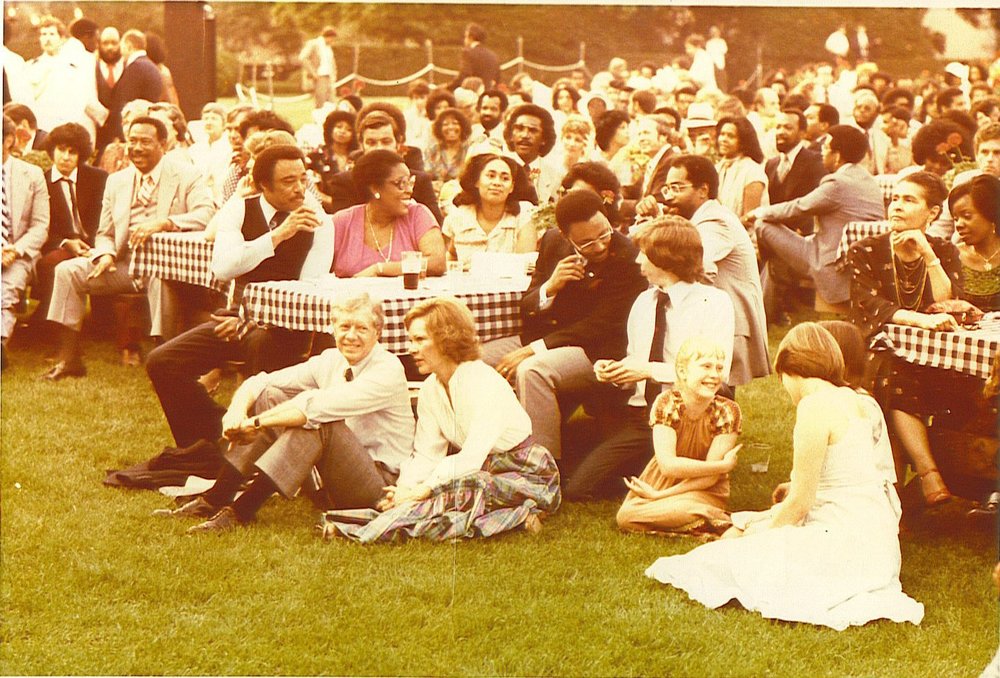

On June 7, 1979, President Jimmy Carter invited leaders of the Black Music community to the White House for a celebration of Black music. The picnic-style event was held on the South Lawn of the White House. Gamble reached out to Clarence Avant, the godfather of Black Music, and Jules Malamud, who was a key figure of the then Black Music Association and the founder of the National Association of Recording Merchandisers to petition President Carter to host a Black Music reception at the White House.

The White House celebration included a who’s who from the Black Music industry with more than 200 guests including Chuck Berry, Thelma Houston, Patti LaBelle, Barry and Glodean White, Clarence Avant, Frankie Crocker, Leon Huff, Tom Joyner, Robert Gordy, Jack “The Rapper” Gibson, and of course, Kenny Gamble, Dyana Williams, and many others from radio and records including Ray Harris, founder of the Living Legends Foundation, then head of Black Music at RCA Records and an active board member of the Black Music Association, who arranged for RCA to be a sponsor of the event. The performers were MFSB (Mother, Father, Sister, and Brother), Sara Jordan Powell, Andraé Crouch, Evelyn “Champagne” King, Billy Eckstine, and Joe Williams with musical direction by Dexter Wansel.

The magic of that afternoon has been kept alive for 45 years as a testament to the strength and depth of Black music which has been a financial stalwart for the global recording industry. Gospel, jazz, R&B, hip-hop, rock, and yes, even country which has roots in the tradition of the Black American experience called “The Blues.”

As we look back at that time and look inside today’s record labels, we see Black music, especially hip-hop, leading record profits, where streaming and downloads reign supreme. Yet we see mass employee layoffs in areas where Black executives appear to take the hardest hit. Today’s rationale from the establishment is that radio isn’t the only way to break records, as it used to be the primary source. This statement may be true, but it also reveals that Black music executives were mainly seen as radio promotion executives.

Whenever record companies “restructure” the areas that contain the highest number of people, Black employees tend to fall on the chopping block. This goes back to the restructuring of major labels after the romance with “Black Music Divisions,” which gave birth to “Presidents” of Black Music divisions because those individuals were never considered as potential candidates for the president’s role at the record labels. As the 1990s closed, the dissembling of the Black Music divisions, which became profit centers and created substantial employment opportunities for Black executives in various areas of the company, which impacted employees both inside and outside of the label, was akin to the destruction of Black Wall Street in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The killing of Greenwood’s eco-center, where Black people were once thriving was no longer in vogue. As a result, the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 killed hundreds of people burned more than 1,250 homes, and erased many years of Black success.

In the record industry, restructuring seems to happen at the end of every decade, resulting in the weakening of the Black executive’s presence and power, especially among Black men. It seems to give a new meaning to the words of the fictional character Peter Clemenza in Mario Puzo’s 1969 novel, The Godfather, portrayed by Richard S. Castellano, who was nominated for an Academy Award for supporting actor in the film adaptation. In a key scene with the fictional character Michael Corleone, portrayed by Al Pacino, Peter Clemenza rationalizes the restructuring and wars among the crime families by stating, “These things gotta happen every five years or so, ten years. [It] helps to get rid of the bad blood.” That scene in The Godfather was a great analogy of the history of Black executives in the record industry.

Is it because the Black music executive’s “usefulness” has always been seen as limited in their ability to excel in the corporate environment? Let’s take a quick look down memory lane on how Black executives got a foothold in the music business at the so-called “Major” labels. Coming out of the 1960s, three labels had most of the market share in what was then called soul music (a step-up term from “Race Music”). The labels were Atlantic, Motown, and Stax Records.

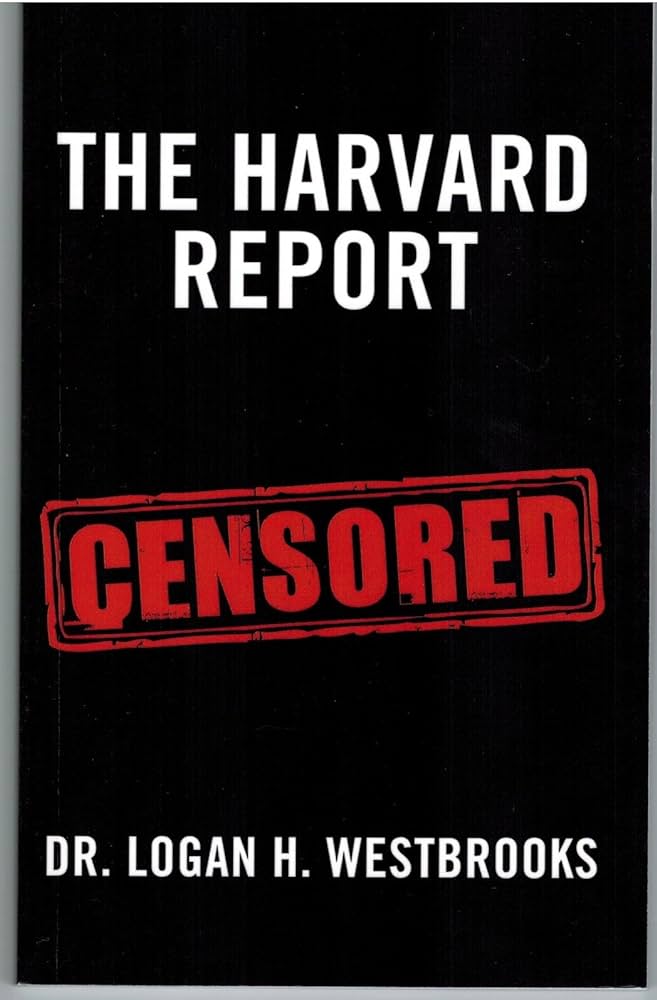

According to the 2017 study of The Harvard Report: Censored by Dr. Logan H. Westbrooks, Atlantic, and Motown Records each had twenty percent of the market share, and Stax Records had ten percent at the time of the report. Black music from the three labels represented fifty percent of the market share including the New York-based Atlantic Records, then founded by Turkish-American Ahmet Ertegun and Jewish-American Herb Abramson. Atlantic Records later merged with Warner Bros., before being acquired by Kinney Parking System, then headed by CEO Steve Ross, who created Warner Communications, which later became Time Warner. Motown Records, owned by Black entrepreneur Berry Gordy in Detroit, Michigan was known as “The Sound of Young America;” and Stax Records (Soulsville USA), then owned by siblings Jim Stewart and Estelle Axton, was based in Memphis, Tennessee, which was referred to as “Soul music” with a Southern base. Stax Records eventually joined Atlantic in a distribution deal and Stax hired Al Bell, a former disc jockey as a national promotion executive. He took on a bigger role and later became the owner of Stax Records. (Check out the HBO documentary Stax: Soulsville U.S.A.).

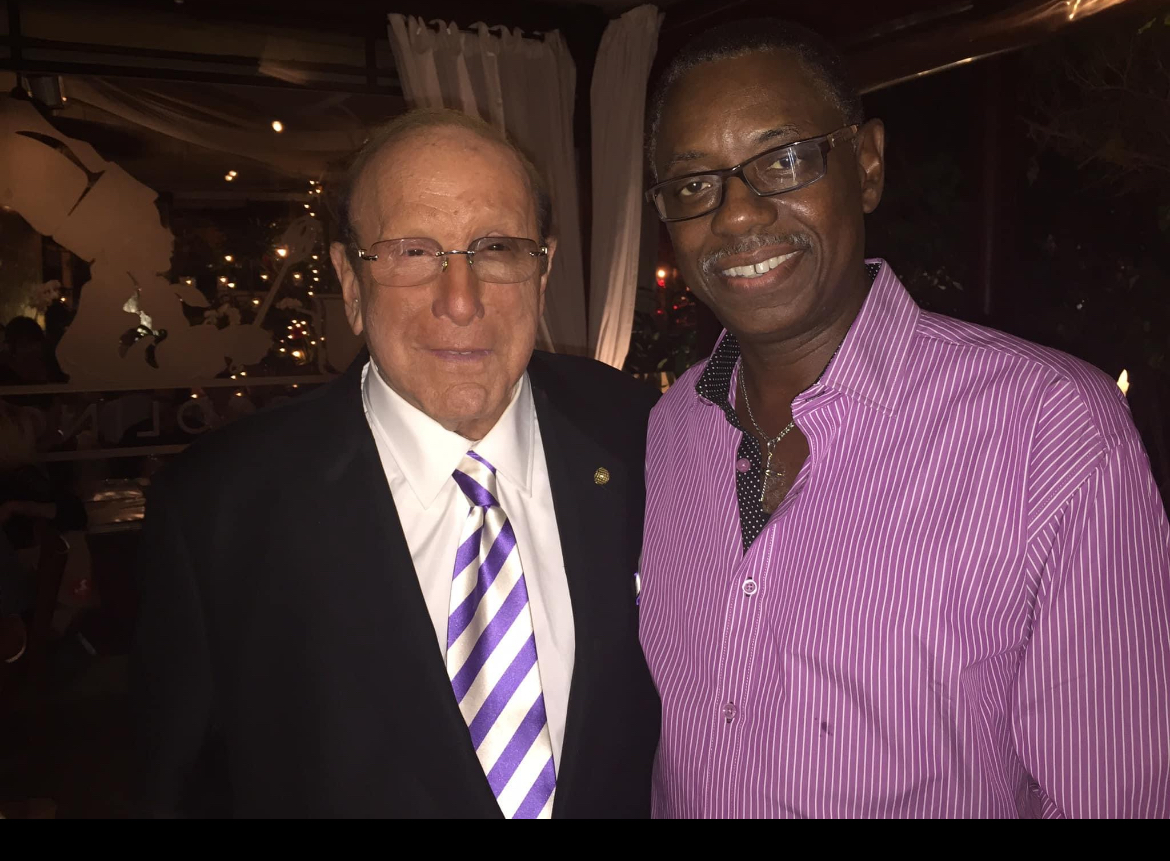

In the early 1970s, Columbia Records was owned by its parent company, CBS Records, and today is widely known as Sony Music Entertainment. Columbia Records desired to expand its interest in building a recording catalog in Black music. In 1972, Clive Davis of Columbia Records commissioned The Harvard Report to research the business of Black Music and to gain a foothold in the profitable enterprise.

Columbia Records’ initial goal was to get at least fifteen percent of the market share within five years (1977). The result was the creation of “semi-autonomous” Black Music departments, where the national director of promotions reported directly to the president of the company. The national director was responsible for hiring A&R, marketing, and promotion executives, and at that time, had control of the “Black Music” team from start to finish. The 1972 Harvard Report study was considered the official blueprint of the new model of the Black Music business and its viability.

Also, in the 1970s, we witnessed the surge of what is known today as “Joint Ventures” and “Distribution deals” with major record labels. Stax Records had its initial partnership with Atlantic and later with CBS; Philadelphia International Records also had a deal with CBS, and Solar Records had a partnership with RCA. Cotillion Records, a subsidiary label of Atlantic Records, already had a home there and began to focus on various sub-genres of Black Music, under the leadership of Henry Allen, who was named President of Cotillion Records in 1980. Allen signed recording artists Johnny Gill, Stacy Lattisaw, Slave and others.

The joint venture partnership became the “A&R” source, providing the music in a deal structure that favored the A&R supplier. Each of the joint venture partnerships proved to be successful. The infrastructure as prescribed in The Harvard Report study was working and soon thereafter other major labels also subscribed to the same joint venture business model, which ultimately expanded their recording roster and business and profit margins. Clive Davis, who was head of CBS at the time continued this same formula at Arista Records, the label he successfully led for decades. He partnered with and offered joint venture deals to L.A. Reid & Babyface (LaFace Records), Sean Combs (Bad Boy Entertainment), and Dallas Austion (Rowdy Records).

Over the decades, these departments grew into whole divisions and the title of national director evolved to vice president, then to senior vice president and later to president of Black music. In 1988, music executive Jheryl Busby earned that title at MCA Records (now Universal Music Group). Then other companies began to make similar moves. The exception was Sylvia Rhone who became president and CEO of East West Records of the U.S. division, a label imprint of Atlantic Records (1990), was named the CEO of Elektra Entertainment Group (1994), one third of the Warner-Elektra-Atlantic superpower label, once owned by Time Warner, and later moved to Universal Music Group. Currently, Rhone is chairperson and CEO of Epic Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment.

In 1991, Ed Eckstine was named co-president of Mercury Records, a title he shared with white music executive Mike Bone. A few years later, Eckstine assumed the role as president of the label. Though a sign of progress was made, in retrospect, it seemed as if it was a way to prepare the industry for a Black executive to take an enormous role as president of a major label.

All the Black music divisions experienced financial windfalls and the unintended happened. In many cases, the billing for Black music departments was more than the other genres. In my opinion, the quest to dismantle the music divisions was to neutralize the influence and power that Black executives were having both inside and outside of the company. These executives became powerbrokers with the artists, Black trade publications, and the allied industries that were crucial to the success of an artist’s overall career, as well as political and social activists and leaders.

In my humble opinion, the blessing and the kiss of death is the mass appeal of Black music in a Black and white world. There was a time when a Black song wouldn’t get on the Top 40 charts unless it was proven first on the Black radio charts. Today, hip-hop singles have worked in multiple formats from the onset. When the senior executive team of the establishment felt that Black executives were no longer needed, the downsizing happened, again. This happened after disco; R&B ruled, then rap, and then New Jack Swing reenergized the Black music scene and charts. Then the “Elvis of Rap,” Eminem sold one million records in the first week. Then every white executive became a “Rap/Hip-Hop expert” because their kids listened to rap music, and white executives felt they knew what Black consumers wanted and needed. As a former senior music label executive, I’ve been in meetings and heard those sentiments shared.

Are we still so enamored with “White acceptance” or the crossing over of our music that in our euphoric state, we lost control? When white executives realized the commercial viability of hip-hop, they began the seizure process, which begins slowly, but methodically, and then Black executives are let go and told that they are not in touch with the music and the culture. Imagine that, as if we don’t know what’s best for our music and those who create and enjoy it.

The move is slick too, as it begins with “We are one” company (code for no need for divisions), and the “integrated system” is introduced. The irony is Black people are always integrated, not the other way around. Then some Black executives are phased out because of duplication of roles or worse “Aged out.” Yes, in their forties or early fifties, Black executives are seen as “Out of touch with music or culture” while their white counterparts move over to other positions and remain in their plum roles allowing them to hold on until the very last cut, giving them the benefit of retiring as millionaires or the very least continuing to provide for their families. How many Black executives compared to white executives remain in their jobs beyond their fifties, sixties, seventies, or eighties?

So, as we celebrate Black Music Month, just a few months from the latest massive layoffs in the industry, I ask the question about the fate of those who work in Black music using Billy Preston’s classic 1970 hit, “Will It Go Round In Circles’? Will the financial strength of Black music once again open multiple opportunities for those from whom the culture emanates? Will Black artists who create the music; stand up for the Black executives who market and promote the music?

Yes, it’s a different world but I’m reminded of the song “Money, Power & Respect” by The Lox featuring DMX & Lil Kim. Black music generates the money, so why don’t Black executives have the power, and where is the respect?

David C. Linton is the chairperson of the Living Legends Foundation, Inc. Currently, he is the program director of WCLK Atlanta, one of the leading global Jazz stations based in the United States. During his more than 35-year career in the recording industry, Linton worked at five record corporations and worked in various genres including R&B, hip-hop, jazz, and gospel. In 2021, the former senior-level music executive was named among the 500 Most Influential Leaders in Georgia by Media Trend. In 2023, Linton was inducted into the National Black Radio Hall of Fame for leadership. In August of 2024, he will be presented with the Radio & Records Lifetime Achievement Award in Atlanta, Georgia.

MORE NEWS ON EURWEB.COM: The Living Legends Foundation Announces Harvey Mason jr., CEO of The Recording Academy as its 2024 Recipient of the Chairman Award

The post The 2024 Living Legends Foundation Black Music Month Series: ‘Will It Go Round in Circles?’ Leadership of the Black Music Executive, the Off-and-On Romance with the Recording Industry appeared first on EURweb.